Hinckley Scribblers Guide to Feedback

All writers benefit from sharing their work and getting helpful feedback from others. However, both giving and receiving critique can seem daunting. With that in mind, Hinckley Scribblers have produced this helpful guide on how to give and receive writerly feedback.

How to give feedback

When a writer shares something with a writing group, it’s best to remember that their piece is usually a ‘work in progress’. The idea of feedback is to give the writer helpful views and suggestions to encourage them to improve and keep writing, rather than to review their work as though it were a final, polished item.

Karen Hertzberg writes on the blog for Grammarly (a free online writing assistant; see Resources) that this requires a ‘deft touch’. She describes how she thought she’d given a useful critique to a writer friend about her novel, only to find out later that the friend had been devastated by her comments and put off from writing for months.

Which leads to the first point:

Encouragement and the art of diplomacy

The tone of comments should always be encouraging. Writers can be very unsure and sensitive about their work and may feel vulnerable revealing it to the scrutiny of others. Even famous authors are not immune to self-doubt, as shown in this quote:

A writer’s discomfort might be accentuated by receiving the feedback in a group environment. It’s therefore important to provide all feedback with tact and diplomacy.

Not all feedback has to be positive. Negative critique is very valuable to a writer, guiding their attention to areas of improvement and allowing them to produce their best work. However, sharing only negative feedback is very discouraging to both the recipient and the group as a whole.

The ‘feedback sandwich’

A ‘feedback sandwich’ method is favoured by many people and organisations, for example the Open University. In this approach, the ‘meat’ of a criticism is sandwiched between two layers of encouraging comments. As well as receiving the negative point, the recipient is encouraged by something positive when they first read or hear the comments, then left with something positive to take away at the end. It’s believed that people are much more likely to take in negative feedback if it’s surrounded by positive, encouraging insights.

Too many comments can be overwhelming, so try to pick out your main points only and say them clearly. Quite often, focussing on the positive aspects will have a disproportionate effect on someone’s improvement and confidence, encouraging them to do ‘more of the same’ and leaving negative points to be resolved by the writer themselves at a later date.

Constructive criticism

It’s easy to praise a writer’s work, but more difficult to point out areas of improvement with the tact and diplomacy mentioned above. All negative critique should aim to be constructive: without the ‘constructive’ part, it is simply critical, which may cause offence to your fellow writers.

The key to this is to read or listen carefully (possibly making notes) and ask yourself what it is that you actually didn’t like about a piece of work. Be specific about what you think needs improvement and the reasons why it didn’t work for you. If you can’t narrow it down, it’s probably not worth commenting on.

For example, consider these two approaches:

“It didn’t work for me”

versus

“I felt the timeline was a bit confusing on my first read through. Would it work better to put the information about the monk’s training earlier on in the piece, so we know he’s become a monk before he meets the traveller?”

In the second version, the problem of the timeline has been highlighted and the reason why it caused an issue for the reader has been identified. The feedback also suggests (tactfully) a possible solution for the writer to consider.

In summary: Explain specifically what didn’t work for you and why, possibly sharing any tips and hints you may have to tackle the issue – with tact and diplomacy of course!

Positive feedback

Always try to find something positive to say. This is vital when giving feedback, because it tempers any criticisms and because it encourages the writer to use effective techniques or approaches even more.

Some questions to ask yourself are considered by Joe Bunting in her blog post ‘How to Stay Popular in a Writers Group’ (see Resources). She reimagines our feedback sandwich as an Oreo biscuit with a criticism cream filling, suggesting questions for the (positive) cookie parts such as:

What is unique or effective about their writing style?

What did you enjoy or respect about their characters?

What is a phrase or paragraph that especially stood out to you? Why?

Some ideas to consider when giving positive feedback

- Your personal reaction – what you loved; favourite thing; resonance; impact; any feelings, experiences, connections, or thoughts evoked

- Plot – effectiveness; twists, surprises, and reveals; complexity; ingenuity; originality

- Structure – title; organisation; beginnings and endings; length; for poems also format, layout, rhymes, and rhythms

- Characters – how believably drawn, portrayal, number, and interactions/relationships

- Dialogue – authenticity, placing, amount, effectiveness, pace

- Descriptions – language, emotions engaged, how unusual, memorable, evocative of atmosphere and setting

- Immersion – authenticity, plausibility, flow, consistency, tone

- Language – vocabulary, style, rhymes and rhythms, appropriateness, uniqueness, pace

- Factual details – accuracy, veracity, interest, educational, enriching

- Idea – take on a theme, originality, context, topicality, thought provoking, links to other work or genres

- Personal meaning to the writer – memoir, anecdotal pieces, subject of expertise/interest

- Production – time and effort put in, research, appreciation for sharing with the group

This is by no means and exhaustive list (as a writer you will no doubt think of many more!) but might provide a starting point for positive aspects to look out for in a fellow writer’s work.

How to receive feedback

This can be summarized in four steps:

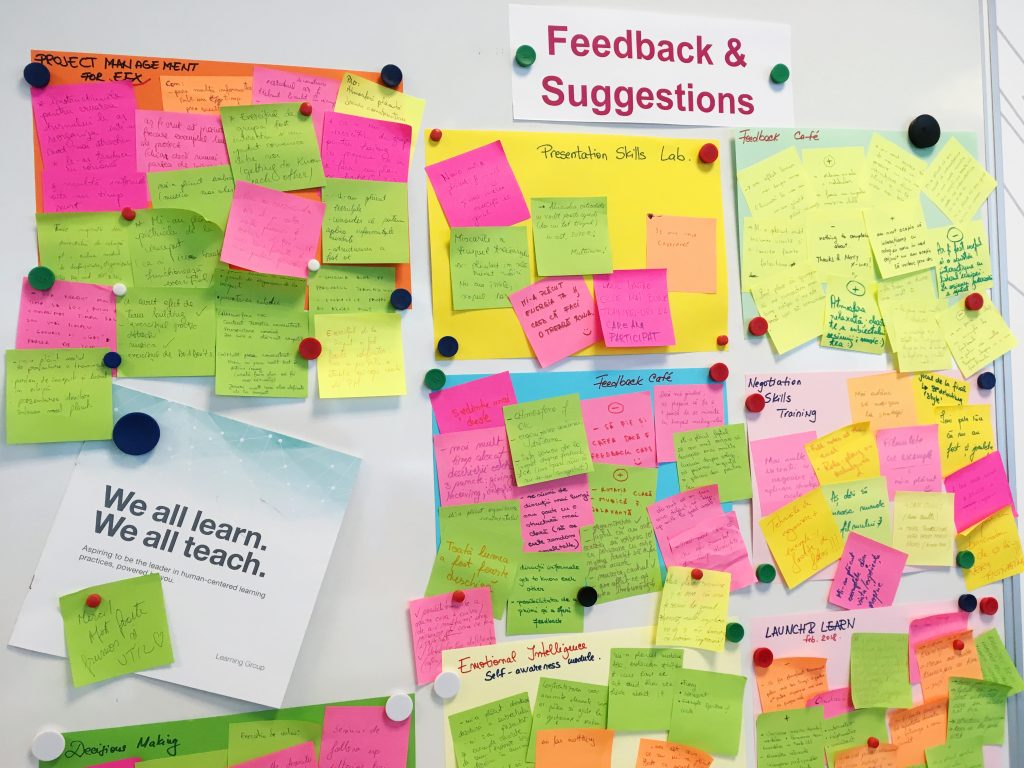

- Consider if there are any aspects or areas of concern you want the group to focus on when reading your writing and, if so, share them with the group. For example, is there a part of your draft you are worried about, or something in your story you feel doesn’t quite gel? Sharing this will help people give you specific feedback.

- As members comment, listen and perhaps take notes. Runaway Writers suggest in their podcast about feedback (see Resources) that the writer waits until the end to respond, once all the feedback has been received.

- Try not to be defensive or take things personally and ask questions if you want to follow up any of the points raised. For example, if someone has made a general comment, ask them to be more specific. You can also take the opportunity to talk about what you wanted to accomplish in your piece.

- Thank people and mention what you found helpful and encouraging. This helps your fellow writers to give even better, more insightful advice in the future. Everyone has different ideas and perspectives and you are of course entirely free to follow, adapt or ignore any advice or suggestions you receive. Feedback is invaluable, but as the writer, you always have the last word!

Finally

Remember that your comments should be intended to encourage and support other group members. We are all here to help one another improve and above all enjoy our writing.